Music and Murder Most Foul – The recording visionary Joe Meek

2500 words • 9 minutes

Think back, if you will, to the moments in your life when you first became aware of music. It might have been when your parents had the radio on in the car, when you attended a school concert, or when you heard a record at friend’s house. It was when you first felt the rhythm, were dazzled by the sounds of the various instruments, and were moved by the harmonies and melodies.

To me, the very best music is described by what I have come to call the Three E concept: It is emotive, ethereal, and evocative. Good music is emotive when reaches deep into our body and soul and stirs us to move and dance. The second E, the ethereal quality of music, is what makes the sound seem as if it is wafting in from a distant world. Those old enough to remember AM transistor radios or Radio Luxembourg recognize the mysterious nature of those broadcasts—as if we were trying to capture a ghost. Third, good music evokes in us thoughts, images, ideas, and memories.

With this, I would like to introduce you to the late Englishman Joe Meek who, in the late 50s and early 60s not only created many of that era’s unforgettable sounds, but who also crafted recording techniques that hundreds of musicians would, in the following years, make part and parcel of their creative expressions.

First, a step backward. To pass time during the Covid-19 months, I listened to a lot of podcasts about the Beatles. Many are surprisingly good and discuss not only their music, but also the cultural and historical context that surrounded the rise of the Fab Four.

The more I listened however, the more I realized that there are some very peculiar aspects to musical fandom—particularly when it comes to the biggest stars like the Beatles, The Rolling Stones, and other major acts.

Time and again I would hear listeners, ranging from casual fans to experts, attest to the astonishing young age at which they were influenced by their musical heroes. Almost as if they were describing a religious conversion, these commentators would bear witness as to how, at the age of 6 or 7 (or even younger!) that their life’s entire course was set in stone by seeing Paul McCartney, or someone from another group such as Mick Jagger, on television. I wouldn’t be surprised that there are some fans who claim that, while they were still in utero, were nevertheless being influenced by the likes of John, Paul, George, and Ringo!

Indeed, such people are adamant that, at age 6, when they saw the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show their lives were forever changed. I don’t mock such individuals though. In fact, I rather envy them for knowing, even before elementary school, exactly what they were going to do in life. I, on the other hand, was undertaking much more mundane things such as riding my bike or watching the original Batman television series and didn’t have the foggiest idea of charting out a pathway for my future career. All I can say is that it must be nice to have been so perspicacious…

For 6 year-olds

I mention this for two reasons. The first is that the music of the early to mid-1960s is among the first that I, and many of the late Boomers, remember hearing. The second is that while recognizing one’s interests early in life can be a good thing, uncertainty also can be beneficial. Not knowing my own future, for example, has served as an ingredient for creative change…or so I hope as I try to figure out what I should do when I grow up.

Joe Meek, born in 1929, was a record producer whose uncertainties about the music business and fascination with sounds led him to explore what was possible in a recording studio. He was a visionary who broke the rules and it was he, and not Frank Zappa or the Beatles, who was among the first to truly imagine the recording studio itself as an integral part of music production—as if it were a musical instrument to be played. Most important however, is that unlike many producers Joe Meek viewed recording as an art and not simply a technical procedure.

The late 1950s were, of course, the start of something that changed the world: Rock and Roll. Little Richard, Chuck Berry, Elvis, Ike Turner, Buddy Holly, and others offered up new sounds for eager audiences whose listening options were, until that time, limited to jazz (nothing wrong with that mind you), classical, and crooners like Frank Sinatra. Suddenly people had the chance to say “Wow. What is it?” and then “I like it!”

As the 1950s rolled over into the 1960s, what a listener heard on the radio was also a bit of anything and everything. Songs ranged from Bobby Vinton’s Blue Velvet to the Paris Sisters’ dreamy I Love How You Love Me to Chuck Berry’s rocking Johnny B Goode Johnny B. Goode to Buddy Holly’s rollicking Peggy Sue. And let’s not forget the reign of Elvis who was the musical king of all he surveilled.

Yet complete modernity had not quite arrived. The British Invasion, and the major stylistic changes that came with it, was three or four years in the future and record making could still be rather primitive. Even the best studios struggled to deliver the sounds that artists and producers were imagining and wishing to bring to fruition.

Nevertheless, behind the scenes innovators like the famed Sam Phillips in his Memphis studio, Meek, and Phil Spector (Note 1) were feverishly exploring what new ways there might be to record music and their hundreds of hours of experimentation and tinkering yielded techniques that are still used today.

Meek, from an early age, had always been puttering about with circuits, radios, and components and, after an early 1950s stint in the Royal Air Force as a radar technician, he settled into work as an audio engineer—a calling into which he poured every ounce of his considerable creative energies. Champing at the bit to try new studio techniques, he started to make his mark in 1956 when he worked on Humphrey Lyttleton’s recording of Bad Penny Blues.

The accepted method of recording music in those days was to place the musicians in front of three or four microphones that were always in the same location. The goal was to give the listener the aural experience as if he/she were sitting directly behind the conductor and while this did produce a consistent sound, it lacked inventiveness, ingenuity, and imagination. Additionally, with very few recordings being made in stereo, mono was the only game in town and the sessions were so formal that the recording technicians even wore white lab coats!

Humphrey Lyttleton

continued playing until his death in 2008.

But on Lyttelton’s recording, Meek departed from the established procedures and brought the microphones much closer to the instruments he wished to highlight. He then used compression to limit the loudest sounds and amplify the quietest ones.

On this recording you can hear how he accentuates the brushes the drummer is using and distorts the piano. The result? A sound that catches the ear by its radical departure from what a listener was expecting to hear—certainly not the drums brought so far forward in the mix and a discordant piano!

While this, and other Meek experiments might sound, no pun intended, extremely basic by today’s standards, his research earned him the reputation of being a maverick. But coupled with a fanatical work ethic and a demanding personality, he brought the studio itself to life and delivered fascinating listening experiences. So revolutionary was his approach and resultant output, that in 2014 New Musical Express, a British trade publication, named him the greatest producer of all time. While many would argue that title should go to Quincy Jones, Sir George Martin, Phil Spector, Brian Wilson, or other greats, this ranking reflects the esteem in which experts hold Meek for his pioneering techniques.

It is easy to get lost in the technical details of Meek’s equipment and recording techniques, and for those who wish to plunge deeper I recommend Barry Cleveland’s outstanding book Joe Meek’s Bold Techniques. Yet whether you are technically detailed or not, you undoubtedly can recognize Meek’s recording basics such as echo, reverb, delay, looping, double tracking, overdubbing, and sound imaging as now being integral to modern music.

Although Joe could neither play a traditional musical instrument nor sing, his talent (some would convincingly argue genius) lay first in envisaging the textures of music and second, having the technical expertise to bring these ideas to fruition. Sure, raw Rock and Roll, the Blues, and Jazz could be breathtaking just by having the ensemble on stage and jamming away, but Joe envisioned something more—a deeper and broader sonic experience.

Over time, he cobbled together a series of recordings into what today we call a concept album. I Hear A New World was Meek’s sonic vision of outer space. Though never released in his lifetime, it is worth listening to at least once just to hear all the sounds that he created—some quite remarkable for the recording equipment of the era. Fair warning however…this really is not music per se, but experimentation so be sure to listen to it through that frame.

Eschewing the early 60s trend of more elaborate and spacious studios (EMI and Decca come to mind), Meek decamped to 304 Holloway Road in London where he set up a home studio above a leather-goods store. It was here that, in 1961, he worked back toward more melodic work and created hits such as Angela Jones and the #1 Johnny Remember Me as sung by John Leyton. During these sessions he would spread singers, instruments, and equipment all over the three-floor flat in his quest to capture the sound he wanted—including in the stairwell and in the lavatory.

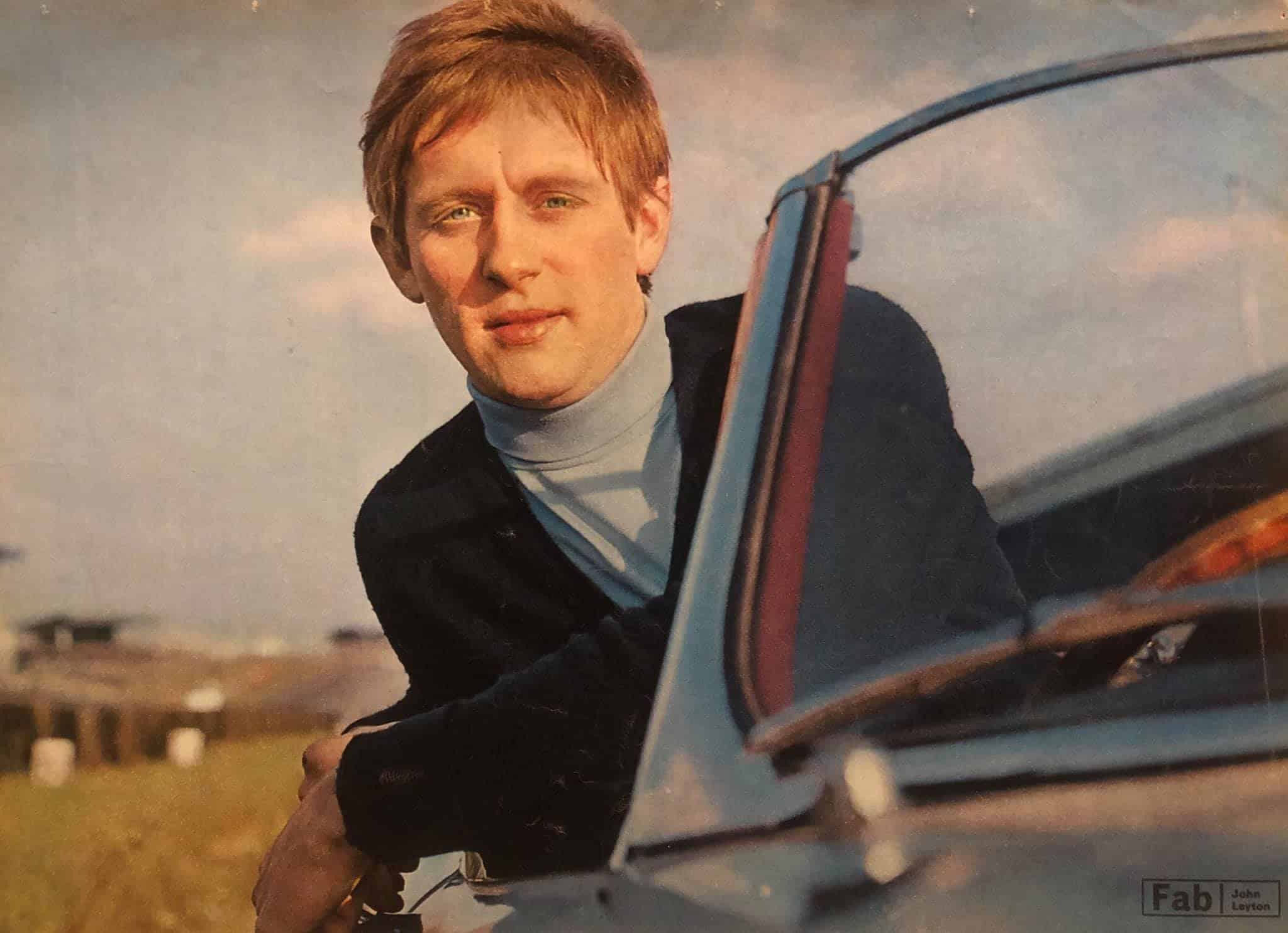

John Leyton

singing Meek’s #1 hit, Johnny Remember Me

Three of my favorite Meek productions were the Flee-Rekkers’ Sunday Date, Houston Well’s Only The Heartaches, and Mike Berry’s outstanding B-side Loneliness. Yes, these sound extremely basic, but deep within them lie the new concepts and techniques that Meek was championing. I find them to be supremely evocative of the early 1960s.

Success led to more success and in 1962 he scored a U.S. and UK #1 hit with Telstar. Inspired by the launch of the communications satellite of the same name, Telstar features a Clavioline—a three octave keyboard that was invented in France in 1947 and which served as a forerunner of sorts to the modern synthesizer. The guitar sound is hauntingly ethereal and, again, evocative of the era. By the way, that is indeed the British drumming great Clem Cattini giving the song its percussive force—apparently including stomping on the stairwell floor.

Sadly, after 1962 Joe Meek’s career was one of decline. He did score another #1 in 1964 with Have I The Right for the Honeycombs—a song I find both cloying and annoying but I will let you be the judge. Nevertheless, even with this triumph his glidepath was downward and he was frequently plagued by money and debilitating mental health issues.

As a homosexual at a time when it was still illegal in the United Kingdom, he felt himself increasingly under pressure in his personal life. Although he ultimately prevailed in a plagiarism charge for Telstar, it took years to resolve and the money was not released until after his death—something that caused him financial distress from 1962 onward.

Added to these worries was possible drug use, most likely amphetamines and barbiturates, and it is probable that he suffered from schizophrenia and/or manic depression. He grew increasingly paranoid in the belief that other record producers had bugged his studio in order to steal his recording secrets and he harbored the belief that the deceased Buddy Holly, to name just one, was sending him messages from beyond the grave. While some who dealt with him from 1962 onward had no difficulties with his personality, many found his behavior increasingly unpredictable and volatile.

Unfortunately, Joe Meek’s life and career came to a gruesome conclusion on 3 February 1967 when he, brandishing a shotgun, murdered his landlady Violet Shelton and then turned the weapon upon himself. He was only 37 years old.

Joe Meek was an experimenter who did not seek to replicate the assembly line practices of the big-name studios and instead strove to create not a catchy and jingly pop tune, but rather a certain sound—no matter how distorted, off-kilter, or unusual. In fact, Meek turned down working with many otherwise promising artists such as David Bowie (David Jones at the time), Rod Stewart, and Tom Jones as he felt they didn’t quite have the sound he was looking for.

Yet fortuitously, even providentially, we may soon learn even more about Joe Meek’s particular genius for studio work. Not long after Joe died, the musician Clive Cooper recovered from the flat nearly 2000 tape reels (4000 hours of recordings) that were stored in old tea chests. He moved them to permanent storage where they have sat for the past 50 years.

In 2020 however, Cherry Red Records took possession of the tapes and is now meticulously working to extract the content and digitize it. Experts are confident that there will be pleasant surprises in store. Here is a short video as to how this labor of love is unfolding: The Joe Meek Tea Chest Tapes

Those who break conventions and sail in new directions can sometimes be hard to understand as they are imagining things that the rest of us cannot fully grasp. Yet they are also the ones who frequently create new and wonderful artistic experiences for us. Joe Meek was one of those visionaries and we, as the listening public, are the grateful recipients of his work.

Happy Listening,

![]()

A note or two

- Sam Phillips and Phil Spector were also major game changers in the world of music. Phil Spector was brilliant but a nasty piece of work who died in jail—also for murder. Phillips, who discovered Elvis, B.B. King, and others was brilliant, racially fair, and a good guy. It takes all types in the music industry sadly. I plan to write about these two so watch this space.

- There was a very good documentary about Joe Meek that appeared on British television in 1991. His brothers were real Forest of Dean chaps—good humored with a twinkle in their eyes. Enjoyable viewing: Joe Meek Documentary

- John Repsch has written an excellent of biography of Joe Meek. It is time well spent.

- In 2008 the movie Telstar hit the screen. It was poor and not at all accurate. I would seriously recommend giving it a pass as I have done the hard work, dear reader, and suffered through it for you. Perhaps a movie studio will one day make a new movie about him. I have no doubt that Tom Hanks will, of course, insist on a part.

- Is there anyone else who thinks that Mike Berry’s outstanding B-side Loneliness could have found a fitting place in David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive? It would have fit in well in that 60’s recreation scene. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Le050qkwI6E

- The pictures of Joe Meek are very copyright protected. Here is what he looked like: https://www.google.com/search?q=joe+meek&client=firefox-b-1-d&source=lnms&tbm=isch&sa=X&ved=2ahUKEwisotTajbv6AhU7FFkFHdo9C24Q_AUoAXoECAEQAw&biw=1920&bih=919&dpr=1#imgrc=vopL5MraPQkDvM