Pink Floyd—A Very English Band | Part I

Dear readers,

Thanks to you, the book I wrote two years ago, Steel Production in Romania 1954 to 1963, shot to the top of the bestseller lists and remained there for nearly 40 weeks. For that I am deeply grateful to you and I hope you enjoyed it. As luck would have it, both fortunate and very unfortunate, I had finished the follow up work, Population Shifts Along the Dnieper River and in the Donbas 1500-2010, just as Russia invaded Ukraine.

Since the appearance of this latest book, these past months have found me in a whirlwind of public speaking engagements in which I am frequently asked to comment on the geo-strategic and geo-political events in Ukraine and Russia. During January 2023 alone, I found myself on twelve different European television programs as I described to the viewers the various elements of the war.

Yet it was during my last appearance, in London, that I was asked a question that I never would have expected. As I was droning on, in my usual soporific style, the urbane British moderator gently interrupted to ask me if I was aware that 2023 marked the 50th anniversary of one of popular music’s most memorable moments—The release of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon.

Ok…time for a confession. I did not actually write books about steel production in Romania or population shifts in the Donbas region. Nor did I appear on European television and I am not even an expert on geo-politics and strategy. I have, however, always wanted to start an article with something like this. Why? Because over the years I have read countless famous writers and columnists who have been quite successful by adopting this annoying affectation with its swanky and superior overtones.

I recall one article from Thomas Friedman of the New York Times, for example, in which he mentions that he was just “jetting back” from Beijing where, according to him, he had yet another earth-shattering insight into what is already obvious to many of us. And who can forget the other well-known talking-heads who love to tell us that they have just returned from Davos, Switzerland or Aspen, Colorado where they were speakers at an important conference. As an average bloke, I find all this name and place dropping to be pretentious even if it is, just for a moment, great fun to pretend that it was me on television acting this out.

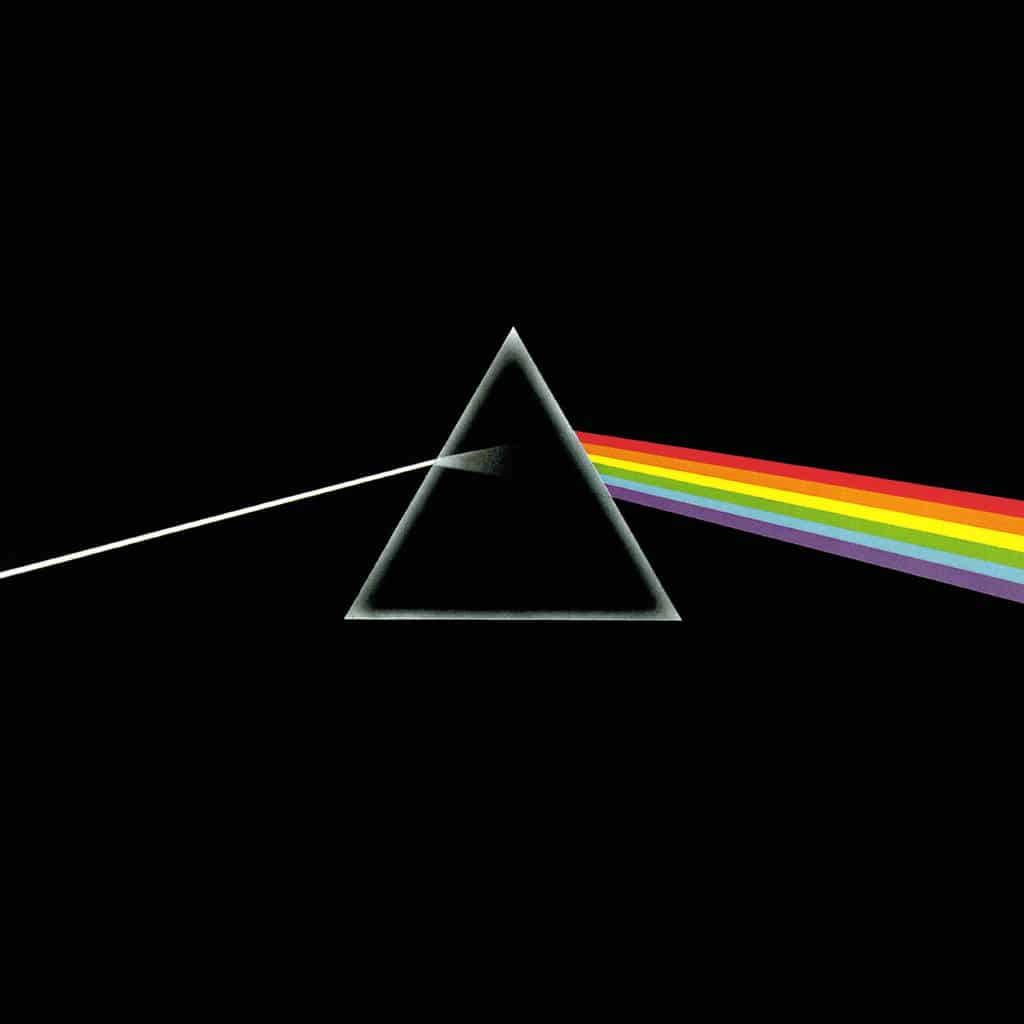

On the other hand, I am indeed aware that 2023 is the 50th anniversary of Dark Side of the Moon. These days, while we as music afficionados enjoy an embarrassment of riches across all musical genres, a good argument can be made that the Dark Side of the Moon is one of history’s greatest recordings. If I might be allowed a cliché, Dark Side of the Moon really is iconic. With its distinctive “prism” cover art, lyrics that have actual meaning, and a coherent theme from start to finish, it is a musical masterwork—one that has sold 45 million copies worldwide and, during the seventies and eighties, remained on the Billboard Top 200 Album chart for 15 consecutive years. More impressively, it sounds as good today as it did in 1973—an admirable feat for even good music can sound dated as the decades pass—drum machine tunes of the 1980s anyone?

Yet while these sales numbers are indeed impressive, the cold figures of “product moved” don’t always reflect an album’s underlying artistry and it is within the artistry where the sheer musicality of Pink Floyd makes Dark Side of the Moon emotive, melodic, and meaningful.

Before we get too far ahead of ourselves however, let’s look at the group’s early days.

The Start of Pink Floyd

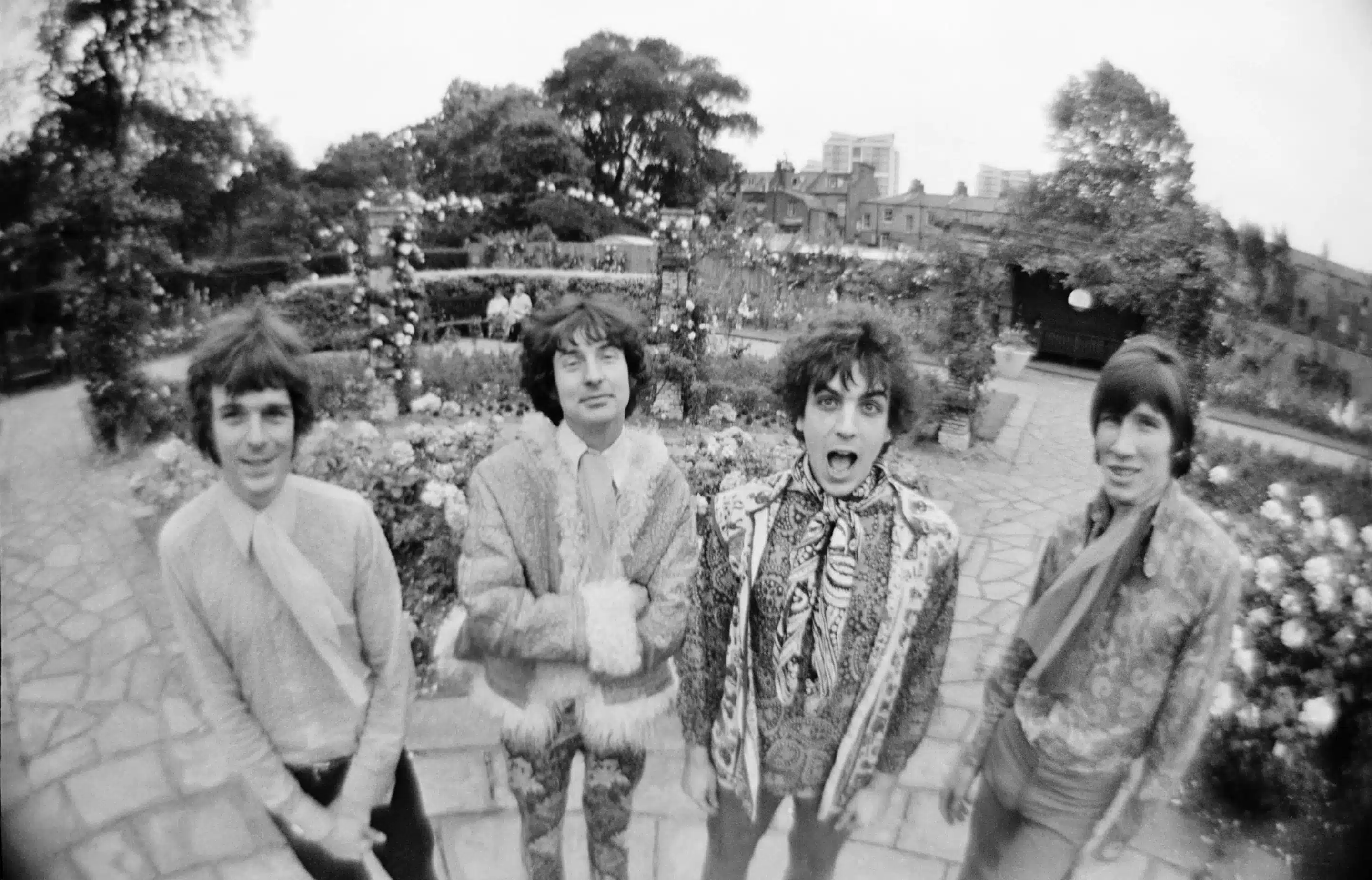

Pink Floyd, a name drawn from the American Blues musicians Pink Anderson and Floyd Council, had its roots in that remarkably fecund period of 1960s artistic England. Not only were the British Invasion groups such as the Beatles and the Rolling Stones in full flight, but countless other creative souls were coalescing around new ideas and new musical directions.

Three of the founding members, bassist Roger Waters, drummer Nick Mason, and keyboardist Richard “Rick” Wright were bright middle-class architectural students who met at the Regent Street Polytechnical Institution in London. Although Wright soon switched his studies to music, the three started to practice together and play gigs wherever they could land them. As was the norm in those days for up-and-coming ensembles, they initially played cover versions of established British and American pop songs while also toying with the elements and styles of the Blues and improvisational jazz.

As it did for many bands, their story could have ended after a year or two for it was quite normal for aspiring musicians to drift away into more stable careers. Here is where, however, the Fates were also hard at work. For it was the arrival of one Roger Keith “Syd” Barrett in early 1965 that set the foundation for the group’s future artistic success.

Syd Barrett, who is now a legendary figure in the history of Pink Floyd, hailed from Cambridge. Even as a youngster he displayed artistic inclinations—particularly in writing and sketching. He was humorous, engaging, and likeable—all of which could be exceptions for the male teenagers of the day in England where being “cool” often meant adopting an aloof and brusk persona. Everyone who knew him readily attested to his charm, wit, and alluring personality. Like other figures such as Jim Morrison (see Note 1), he is best described as having “it” — that personal magnetism that friends and strangers alike find so attractive.

In 1964 Syd had decamped to London to enroll in the Camberwell College of Arts to study painting (see Note 2). Nimble minded and adroit with wordplay, he was soon spending his free time combining his guitar skills with his burgeoning interest in writing lyrics. Not long afterward, around early 1965, he joined forces with Waters, Mason, and Wright where he not only conjured up the name Pink Floyd for the ensemble but, more importantly, gradually shifted the group’s emphasis on pop, Blues, and jazz toward one centered on psychedelic and progressive themes.

Such labels as “psychedelic” and “progressive” can sometimes be so broad as to be meaningless, but as a rough guide psychedelic music was linked to the idea of altered states of consciousness through the use of LSD, cannabis, mescaline and other substances. Progressive music, on the other hand, freed itself from the straitjacket of the 3-minute commercial pop formula by adopting a much longer lyrical and poetic style. Like jazz and classical music, these new forms were much more suited to listening and reflection instead of just dancing. (See Note 3)

London, of course, was a center of a vibrant psychedelic/progressive underground scene and one in which Pink Floyd, through late 1965 to 1968, quickly became a popular practitioner. Frequently performing at a club called the UFO (pronounced you–foe), the group added visuals and unique lighting to its show. While rudimentary by today’s standards, those loopy oil-dropped light images were something new and, to borrow from the lingo of the period, were rather “far out.” Add Syd’s lyrics to this mixture of light and sound, and the listener was in for a totally new kind of concert experience.

While the group was experimenting musically, Syd was equally as diligent in his investigations of LSD, weed, Mandrax (the British version of Quaaludes), and other substances. Debate rages hotly even today as to the real levels of Syd’s intake of drugs but, either way, by 1966/1967 he was aflame with creative brilliance while simultaneously stepping dangerously close to the edge of mind-altering experiences.

Under Syd’s inspiration, the group released two singles in the Spring of 1967: Arnold Layne and See Emily Play which were followed shortly thereafter by what critics and fans alike consider one of rock’s pivotal recordings. The Piper At The Gates Of Dawn, or simply Piper as it is often called, blends the bands long form improvisational work with Syd’s shorter and quirkier compositions. Still very much worth a listen in 2023 both for its excursions into new sonic territory and its lasting influence on other groups, many listeners consider Piper to be Syd Barrett’s crowning achievement as the guiding force behind Pink Floyd. (See Note 4) What is doubly enjoyable is that Syd did not try to sing like an American and for those, like me, who are Anglophiles, the accent is a pleasant linguistic time capsule of Cambridge and London in the mid 1960s.

Unfortunately, during the recording of Piper, Syd started to be afflicted by severe mental problems. It might have been schizophrenia, the drugs, or the fear of the pressures of becoming a rock star, but there is little doubt that LSD and Mandrax could, and most likely did, significantly worsen the symptoms of his mental difficulties. Sadly, he was never professionally diagnosed or treated, but irrespective of what was causing his mental deterioration, his decline was rapid and precipitous. The outgoing and humorous Syd of old quickly became a Syd who was far more reserved—with many saying that he was distant and withdrawn.

Examples were rife of him losing situational awareness and not being able to accurately judge the passage of time or, occasionally, not even knowing where he was. Roger Waters recounts that once when they were walking down a street in Los Angeles that Syd thought they were in Las Vegas. Needless to say, this led to serious problems as a performing musician. His bandmates, both out of frustration and not knowing what to do with someone struggling mentally, simply began to perform without him. At first, they thought he could assume a role similar to that which Brian Wilson had with the Beach Boys—remaining at home and writing while the group traveled from gig to gig. Even this however, did not work out as Syd wrote fewer and fewer songs—a tragedy for someone so gifted with words.

Syd started work on about half of the group’s second album, A Saucerful Of Secrets, but the band had to finish the rest without him as he withdrew into a self-imposed exile from society. While he did return to the studio in the early seventies to record two solo albums (See Note 5), he eventually drifted back to Cambridge where he was cared for first by his mother and then eventually his sister. He would occasionally be spotted cycling around town, but he was exceptionally private and after 1971 he never again interacted with his former bandmates or gave interviews. Syd died in 2006 from the complications of diabetes and we will never know if he every truly realized how much the music world was indebted to him for being the creative spirit that set Pink Floyd on the path to stardom. See Note 11 for a link to the last real interview with Syd.

If one is unfamiliar with his work, might I suggest three recordings to dabble in: The single Arnold Layne, the Piper At The Gates of Dawn album itself, and the song Remember A Day from the group’s second album A Saucerful of Secrets. Although Remember A Day was written and sung by the keyboardist Richard Wright, Syd plays slide guitar on the recording and it is an excellent 3-minute example of that era’s sound and the band’s vibe. It remains my favorite from the early Floyd recordings and I am confident that you will enjoy it.

Unfortunately, during the recording of Piper, Syd started to be afflicted by severe mental problems. It might have been schizophrenia, the drugs, or the fear of the pressures of becoming a rock star, but there is little doubt that LSD and Mandrax could, and most likely did, significantly worsen the symptoms of his mental difficulties.

The arrival of David Gilmour and Roger Waters new role as lyricist

The departure of Syd Barrett from Pink Floyd is an event that even today, 55 years later, still sparks the most intense debates. Should the group have done more to have helped him? Should they have changed the name of the band when they continued on without him? Why didn’t they reach out to him as the years went by?

These, of course, are questions that can never be answered. Fortunately, the English documentarian John Edginton interviewed the remaining band members in 2001 and has been very gracious in posting these thoughtful memories of that time. From them, we gain a deeper understanding of what was happening to Syd and the struggles of those around him to make sense it all. This is excellent viewing not only for the musical history, but also for the humanity it reveals in his bandmates. See Notes 6 through 10 below for the links to these interviews.

Just before Syd’s departure, Waters, Mason, and Wright realized that they desperately needed someone to replace him and so they invited experienced guitarist David Gilmour, also from Cambridge, to join the band. While David overlapped on three or four gigs with Syd and on parts of the recording of Saucerful of Secrets, the changeover from Syd to David occurred quickly.

As with any musician entering an established band as a “new guy,” it took a bit for the band members to sort out the new arrangement. David felt, quite naturally, to be an outsider and the group had to decide whether he should just sing Syd’s lyrics and play his guitar parts, or if he should work on new material instead. Well, as history would reveal, David Gilmour’s excellent guitar chops and solid voice allowed him, in good time, to step out from under Syd’s shadow and make his own mark.

The real problem for the group, however, was that Syd Barrett had been the one writing the lyrics and that while Waters and Wright had contributed some songwriting, it was Syd who had carried the bulk of the wordsmithing load. Obviously for the band’s long-form instrumentals this was not a problem, but it certainly was a serious one when the group wanted to express its ideas in words. Ah, but alas! Here is where Roger Waters stepped into the breech in a very big way.

As I mentioned earlier, these were bright young men with solid educational backgrounds. Listen to the interviews with them over the years and you will hear words like ambit, remit, funereal, undulation, acidulous, and apposite. Rarely does one hear such well-spoken rock stars.

While one might think that such a vocabulary is best suited to academic writing or the fun of a crossword puzzle, what it really meant was that Waters, Wright, Gilmour, and Mason were not intimidated by words and instead fully realized their power to communicate ideas. Just like with their instrumental long-form numbers, they were willing to use lyrics to form entire themes and not just fill an album with unrelated songs.

Roger Waters had lost his father in WW2 and it had, as was sadly the case for many lads of that era, left deep scars. Add in some nasty experiences at school and he grew intense in both his thinking and personality—with some arguing that he became a bully in his own right.

As he started to write, he worked this trauma into his lyrics. War and the loss of his father are recurrent themes as are the concepts of our mortality, struggles to effectively communicate, and the unending “us versus them” mentality that is seemingly encoded in our DNA.

Yet dear reader, this is where we enter the brilliance of the post Syd Barrett Pink Floyd era. For it is here that we witness the perfect counterpoint, no pun intended, of David Gilmour’s and Richard Wright’s beautiful melodies set against the intensity of Roger Water’s lyrics. Pink Floyd was now a group in which the musicians and the lyricist complemented each other in just the right measure.

Pink Floyd left the psychedelic scene after Syd’s departure. Naturally hard-core fans, as they so often do, accused the band of “selling out to the man,” but Waters, now taking an increasing role as the leader in addition to that of lyricist, had other plans and visions for the group and so they simply closed this chapter of their history and moved on. Other than Syd, and obviously many in the audiences, the remaining members of the band were never really that far into the drug scene anyway. Instead, they were ambitious lads who were beavering away working long hours to make music their career.

Echoes as a precursor to the Dark Side of the Moon

To keep the story moving, I’ll speed ahead to the year 1971. Pink Floyd releases its sixth studio album Meddle on which the entire second side is given to a song entitled Echoes. Based on Roger Water’s ideas of human communication, it is a musical journey that serves as a historical signpost marking out the band’s direction for what was to come two years later in Dark Side.

Much to the immense benefit of humanity, we have a video to go along with the audio. In October of that same year the band, in a rather unusual anti-Woodstock gesture, performed in the empty ancient Roman amphitheater in Pompeii, Italy. The footage was edited and made into a movie and it is here that we have the full 24-minute clip for Echoes in which the listener is treated to the exceptional harmony of Gilmour’s and Wright’s voices, magnificent guitar soloing, and melodic keyboard work. Nor can one overlook Nick Mason’s mesmerizing performance behind the drum kit. It is, quite simply, a display of four musicians at the top of their game. See Note 12 regarding the absence of Tom Hanks in this film.

Let’s take a pause for a moment. The table has now been set for Part 2 in which I will look at how Dark Side of the Moon was created as well as the band’s history through the 1970s and beyond.

Until then. I wish you happy listening!

![]()

- I described Jim Morrison in this article: Jim Morrison and the Doors

- Many famous English musicians were, in their youth, art school students. Along with Syd Barrett one can add the names of John Lennon, Jimmy Page, Eric Clapton, Pete Townsend, David Bowie, Christine McVie, Cat Stevens, Keith Richards, Jeff Beck, and of course Freddy Mercury. The list is quite long.

- Under the psychedelic banner we find such groups as The Byrds, Jefferson Airplane, and the Yardbirds. Names you might recognize in the progressive movement are YES and Genesis as only two of many. The problem is that if I mention one there are, quite literally, twenty more of your favorites who also deserve some ink. Perhaps I will tackle that subject in another article.

- The true psychedelia fans of the time who had witnessed the long stage performances of Syd and his bandmates at places like the UFO were quick to climb upon their high horses and claim that Piper did not do justice to the live experience. Well…sorry, but a vinyl album could only contain around 40 minutes of quality recording so there was not too much that the band could do to replicate a live concert.

- Syd’s two post Floyd albums were The Madcap Laughs and Barrett. Both of these were released in 1970. In 2004 a compilation of five of his songs from a previous BBC radio program and three newly discovered ones were released as The Radio One Sessions.

- The English documentarian John Edginton has been most gracious in uploading to YouTube the interviews he conducted with Waters, Gilmour, Wright, and Mason in 2001 regarding Syd. They are immensely enjoyable and the one with Nick Mason, in particular, reminds you of two English gentlemen sitting in a pub having an intelligent, humorous, and thoroughly rewarding chat.

- Interview with Roger Waters regarding Syd Barrett

- Interview with David Gilmour regarding Syd Barrett

- Interview with Richard Wright regarding Syd Barrett

- Interview with Nick Mason regarding Syd Barrett

- Mick Rock wrote this short piece for Rolling Stone in 1971. It was, from all that I can determine, the last real interview with Syd. Written in the style of Maureen Cleave’s interview with the Beatles, it is in retrospect rather haunting: http://www.sydbarrett.net/subpages/articles/madcap_who_named_pink_floyd_roll.htm.

- Surprisingly, the American actor Tom Hanks was not in the Live at Pompeii film. I know…it was a shock to me as well. Unfortunately, no one has been able to explain his conspicuous absence and Tom has, to this very day, offered no comment.

Thanks for part one of the Pink Floyd story. As usual in your musings of music, you move me behind the songs to meet the people. (It isn’t always as good as the music, is it?) Glad you do, and glad to be able to read your take.

I’ve never before explored the complete oeuvres of the band. You’ve pushed me into it…and I shall be forced to listen to the magical pairings of Waters’ poetry with Gilmour and Wright’s melodies.

Looking forward to part two!