Pink Floyd—A Very English Band | Part 2

2600 words • 8 minutes

Fellow readers and fans of Pink Floyd,

I often think that I am living life backwards. While I was a serious and dedicated pessimist as a young man, now that I am older, I am quite an optimist. I say this is backward because men often become crankier as they age. You know how they are—shaking their fists at the television and loudly announcing, to anyone who has the misfortune of being within earshot, that the younger generations are ruining the world. Yet when I meet today’s young, I am impressed by their talent and motivation. Sure, they will make mistakes just as we have, but I don’t think we are facing the zombie apocalypse quite yet. I could be wrong, but at least I will be cheerful about it.

I actually enjoyed my time as a pessimist as I secretly harbored aspirations of becoming a pretend intellectual—a period during which, for example, I enjoyed discussing the writings of the great German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer (1788 to 1860). If his name does not ring a bell, let me introduce you to the man whose collection of writings are described as being “an exemplary manifestation of philosophical pessimism.” See Note 1

Although I never read a single page of his seminal work The World as Will and Representation, as only a genuine intellectual would do that, I did enjoy his much shorter and more readable Studies in Pessimism. Schopenhauer believed that the world is a very flawed and ill-conceived thing but, since we are already here, we might as well get through it the best we can.

Schopenhauer wasn’t all Mr. Negativity however. He was a bright fellow who thought deeply about a lot of different topics and, in addition to German, he understood French, Italian, Spanish, English, and of course Latin. He was also one of the first Western philosophers to take a keen interest in the Indian philosophical traditions—so much so in fact, that he made a serious study of the ancient Hindu texts the Upanishads. Now while there is some debate as to whether he ever tried to learn the Sanskrit of the original writings, he did read the Latin translations of them and that alone earns my highest respect.

I imagine that you are now asking yourself what in the blazes this exceedingly long and perhaps pointless introduction has to do with Pink Floyd? Frankly I’m not sure, but I hope that by the end I will be able to figure out a connection.

We find ourselves in 1971

Speaking of Pink Floyd, when we were last discussing the quartet, we saw that 1971 had been a busy year for them. They had just released the album Meddle and toward the end of the year they filmed their outdoor concert in the empty amphitheater at Pompeii, Italy. The days of Syd Barrett and their performances at the UFO in London were now in the past. David Gilmour had settled in comfortably as lead guitarist and vocalist, Roger Waters had found his stride as the main lyricist, and Nick Mason and Richard Wright were providing solid musicianship on the drums and keyboards. All of the bandmembers were curious experimenters in the studio and they were now itching to explore new ideas. Waters, in particular, wished to set aside the group’s reputation as mere practitioners of “space rock” and wanted instead to continue to put his thoughts into thematically linked songs—in other words a concept album.

And it is here, good reader, that their studio sound experiments and their desire to explore different ideas combined to form the basic ingredients of what was to become the Dark Side of the Moon.

Naturally this did not all fall into place overnight, but by the end of the year all four band-members were perfectly aligned musically, creatively, and in their willingness to constantly refine songs. To put it simply, they now had the fuel in the tank to propel them toward the success of Dark Side.

As the band prepared for a tour of Britain, the United States, and Japan, Roger Waters called a meeting at drummer Nick Mason’s London home in order to ask the others what their biggest worries in life were. Naturally the pressures of touring and the perceived greediness of record industry executives ranked high on the list, but so did death, the rapid passage of time, mental instability, and the insecurities of not feeling as if they were accomplishing anything meaningful in life—all of which were pretty introspective concepts for young men still in their twenties! Grim as the topics might have been, the group decided they would nicely serve as the theme of an album. Furthermore, they decided to address them as clearly and directly as possible. Unlike in previous days, there would be no room for obliqueness in the lyrics.

While this process of deciding on a new album might sound perfectly normal, the band went about it differently than most groups. In those days the standard practice was to first record the album and then go on the road to perform and promote it. Roger Waters flipped this by folding the band’s new material into the existing tour setlist so that the group could change and refine the songs as they went along. Once they had the wrinkles worked out and had a good idea of what was working well, they could then repair to the studio start the actual recording process. And this, much to our benefit, is exactly what they did!

In the studio amidst a busy touring schedule

To gather material for the project, they combined elements of songs that they had been working on over the months. What became Breathe and Us and Them were previous ideas, while for Money Roger Waters introduced tape loops that he had cobbled together at home. The album starts and ends with the “sound and feel” of a human heartbeat, but in between are ten songs that take the listener on a journey through the challenges of life. Initially entitled Dark Side of the Moon: A Piece for Assorted Lunatics, the group premiered the work on the 20th of January 1972 in Brighton, England. A month later, on the 17th of February, and a full year before the release of the actual album, they performed the entire set for the press at London’s Rainbow Theatre where it was, needless to say, very well received. See note 2

It was not until late May of 1972 when they finally entered the EMI’s famous recording studio (now known as Abbey Road Studios) to lay down tracks. Over the next eight months the band spent about sixty total days, spread out over four main sessions, to get things where they wanted. As is often the case, the recording sequence differs from the final album sequence and Dark Side was no exception; Us and Them was the first track recorded, which in turn, was followed by Money, Time, and the Richard Wright composition, The Great Gig in the Sky. Although there is little doubt that the band would have preferred to have stayed in the studio cracked on with the recording work, they had touring and other commitments to fulfill so the remaining tracks would have to wait.

In fact, it is truly remarkable just how busy they were in 1972.

Amid the Dark Side recordings and touring, a full plate by anyone’s definition, they found time to decamp to France to record yet another album, Obscured by Clouds, that served as the musical score to the film La Valleé. Yet despite there being no time for rest, they kept their focus and completed the last studio sessions during January 1973. Six weeks later, on the first of March, the album was finally released to the public where it immediately met broad commercial and critical fanfare.

The happiest of days when the going was good!

Some of the highlights

Of the ten songs on the album, every listener is certain to have a favorite passage or two. It is widely agreed however, that some of the highlights of the recording are:

- The young Alan Parsons as the record’s engineer. Alan had been hired by EMI Studios at the tender age of 18 in 1967 where he gained experience working on Beatles’ sessions. He quickly displayed a variety of recording and musical talents and proved to be the perfect fit to work with the band on Dark Side. Alan was pro-active in his suggestions, worked well with the others, and was faultless in teasing out the sound the band was looking for. Success, as always, is in the details and Alan had many in his bag of tricks. It was he, for example, who had recorded the chiming clocks that are heard in the introduction of Time.

- Clare Torry’s unforgettable vocal performance on Great Gig in the Sky. Recommended by Alan Parsons, Clare was originally paid the unimpressive standard studio rate of about 30£ (about $500 today) for her work. On the day of recording, the only guidance the band could provide was David Gilmour’s suggestion to sing emotions instead of words—which, of course, is exactly what she did in delivering one of popular music’s most distinctive vocal performances. Oddly, she thought she had badly failed in her efforts. None of the band-members gave her any positive feedback (shame on them) and she was certain that her performance would be cut. It was only later, after buying the album, that she realized that she had succeeded beyond all expectations. See Note 3

- Roger Water’s novel idea of posing questions to various studio personnel and then using their replies as background voices throughout the recording. Those are the actual voices of equipment technicians, the studio doorman, and other musicians that we hear.

- While synthesizers were not new to rock music, these were still the early days of studio electronics and the group expertly employed them on tracks such as On the Run, Brain Damage, and Any Colour You Like.

- Music fans seem to either love or hate the saxophone. In fact, many Belgians wish that their fellow citizen, Adolphe Sax, had never invented the instrument in the first place. However, even the fiercest sax critics concede that Dick Parry’s melodious work on Dark Side was the right instrument, at the right time, and in just the right measure.

It can be a bit of a Fool’s errand to concentrate too much of picking favorites from the album. In fact, I would argue that the band intended for the recording to be listened, and then judged, not in snippets or individual songs but as a whole—from front to back and from start to finish.

In the documentary Pink Floyd: The Making of The Dark Side of the Moon, David Gilmour wistfully wonders aloud what it must be like to put on a set of headphones and hear the album for the very first time—something that he as one of the creators never had the chance to do. This perhaps sounds a bit philosophical, but it is an area where we have the advantage over the artists. They were, after all, the ones who were down in the weeds for month after month writing and recording the album—a period during which they probably grew rather weary of it at times. We, on the other hand, get to enjoy this gift of the gods in the form of the finished and polished product.

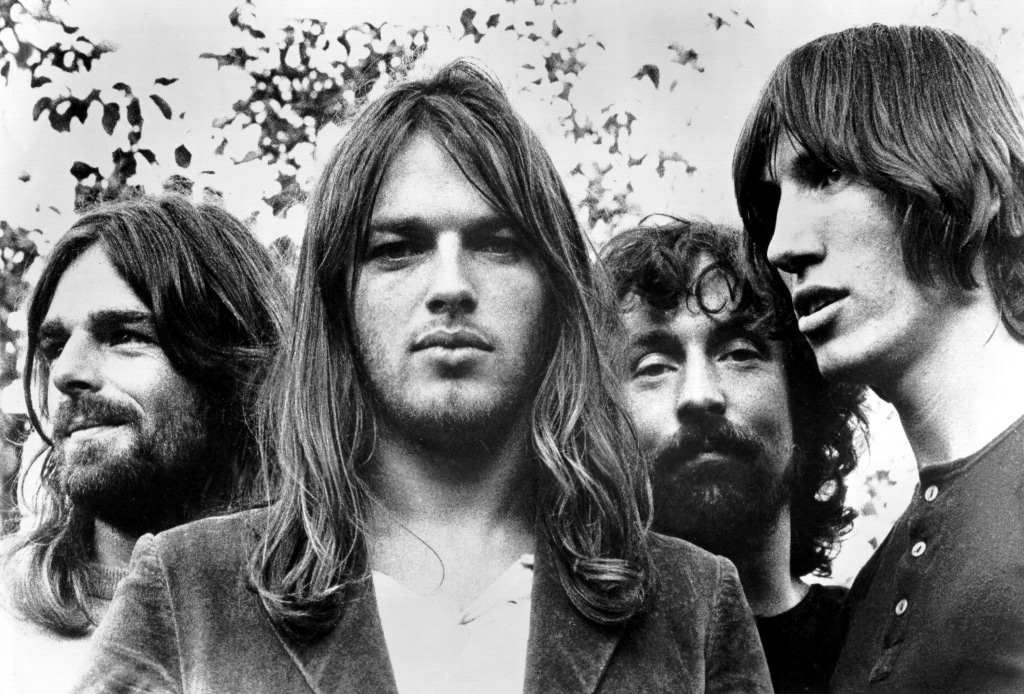

Being a famous band always means a lot of publicity photos

The lyrics versus music debate

It is said that the seeds of discord always lie close to the heart of success and many of you are familiar with the famous feuds that Roger Waters and David Gilmour engaged in after the mid-1980s. What had started as small differences of interpretations grew into full-scare arguments. What was more important—the lyrics or the melody? Fortunately, however, these tensions were at a minimum during the Dark Side sessions and the band was in complete agreement for the final mix of the album.

Yet, even if it is nothing more than an interesting thought experiment, I enjoy pondering the lyrics versus music debate. Is it the underlying keyboard melodies of Richard Wright that strike, no pun intended, just the right chord for you? Are you stunned by David Gilmour’s emotion-laden guitar work? Or is it Water’s trenchant and mordant lyrics that are the most memorable?

True, it is the combination of all of them, along with the highlights I mentioned above, that make Dark Side a brilliant recording, but we are, to paraphrase Waters, only ordinary humans after all. This means that music is like a sonic Rorschach test and what you hear and appreciate can be quite different from the next person. With that in mind, I offer you my humble opinion and ask you for your thoughts.

I admit to being most moved by the melodies. That makes me more of a “Gilmourian” if you will, and I argue that it was Gilmour and Wright who crafted the Pink Floyd sound of the early to mid-1970s. Perhaps I am a musical simpleton, but I almost always find the lyrics to be secondary to the melody, structure, tonality, rhythm, and other musical elements.

This is not to deny the importance of lyrics. What would, to take easy examples, songs such as the Beatles’ Yesterday and Eleanor Rigby be without the words? What about a classic tone-poem like Gordon Lightfoot’s The Wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald that is 100% dependent on the story line? Again, I do not mean to diminish Water’s contribution as he was more and more the driver and leader of the band. I’m simply saying that while words in songs can be clever, I probably am not going to base my life’s decisions on them. As an aside, how often have you run across the legions of internet commenters who announce to the world that a song’s lyrics “have changed my life!” Ah, how I envy the young at times…

I’ll go one step further and admit that it was only recently when I re-read all the lyrics to Dark Side, that I was able to understand what, for example, they were singing in the chorus of Us and Them. Perhaps, as many of my teachers scolded me when I was young, I need to “listen up” and discover what I have been missing all these years instead of just following the tune.

Before I leave you, can you imagine Roger Waters and Arthur Schopenhauer having a few chats down at the pub? Both wanted, even intellectually needed, to get to the root of ideas and were not afraid to ask the questions necessary to get there. Yet somehow I have the idea that at some point the great Schopenhauer would have said “Roger, its ok to just enjoy the music.” “David, Richard, and Nick, really do add a magic element to it all and if I might quote Duke Ellington: ‘It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing.’” “Remember Roger, at times its all just fine to let the music speak louder than the words!”

Should you wish, dear reader, I would be pleased to write a third part to this series in which I could look at the band post Dark Side and describe what challenges and serious divisions the band has faced since. I look forward to your thoughts.

With that, and as always, I wish you enjoyable listening!

![]()

- The long-form explanation of his life and thinking: Schopenhauer

- Here is a 1972 bootleg copy of a concert they gave at the Rainbow Theatre in London. Rainbow Theatre Pink Floyd

- Many years later Clare Torry was awarded undisclosed out of court settlement for royalties for her contribution to Great Gig In The Sky.